The Monroe Doctrine Returns: What it could mean for business in the Americas

For much of the past three decades, Latin America lived in a strategic grey zone.

The United States was focused elsewhere. The Middle East, then Asia, then domestic instability. Engagement with the region narrowed to migration and narcotics, while long-term economic integration faded from Washington’s strategic focus. Into that vacuum stepped China, not with ideology, but with capital, demand, and infrastructure.

That balance is now shifting.

The recent U.S. intervention in Venezuela marks the most explicit assertion of U.S. power in the region in years. Whatever one’s view of the legality or optics, the signal is unmistakable: the United States no longer sees Latin America as peripheral to its strategic or economic future.

To understand why this matters and why it may ultimately be constructive for U.S.–Latin America business integration, it helps to remember that this is not the first time the Monroe Doctrine has moved from principle to practice.

From Doctrine to Corollary

When the Monroe Doctrine was articulated by James Monroe in 1823, it declared the Western Hemisphere off-limits to external powers. It was a statement of intent more than enforcement, as back then the US didn’t have the military power to assert herself over the great European powers.

That changed in 1904 with the Roosevelt Corollary, which asserted the U.S. right to intervene in Latin American countries to prevent instability or foreign interference. This was not theoretical. It became policy, especially in Central America, where proximity, trade routes, and strategic infrastructure made disorder unacceptable from Washington’s perspective.

Central America: Where the Doctrine became real

Central America was where Monroe logic became operational.

In Nicaragua, U.S. Marines occupied the country for extended periods in the early 20th century, shaping political outcomes to protect American commercial and strategic interests. What began as debt oversight evolved into direct influence over governance.

In Honduras, repeated U.S. interventions were tied to protecting American-owned agricultural enterprises and ensuring political stability favourable to U.S. trade, giving rise to the term “banana republic,” a reflection of how economics and sovereignty became intertwined.

In Panama, the U.S. supported Panama’s independence from Colombia in 1903 and retained control of the Panama Canal Zone for nearly a century. Control of critical infrastructure in the hemisphere was treated as non-negotiable.

These actions were often controversial and left lasting political scars. But they established a precedent that shaped the region for decades: when Washington perceived instability or foreign influence near home as unacceptable, it acted.

The Doctrine didn’t disappear, it went dormant

By the late 20th century, this interventionist posture receded. The Cold War ended. Globalisation accelerated. Markets replaced doctrine. Latin America faded from U.S. strategic doctrine.

In that absence, China showed up.

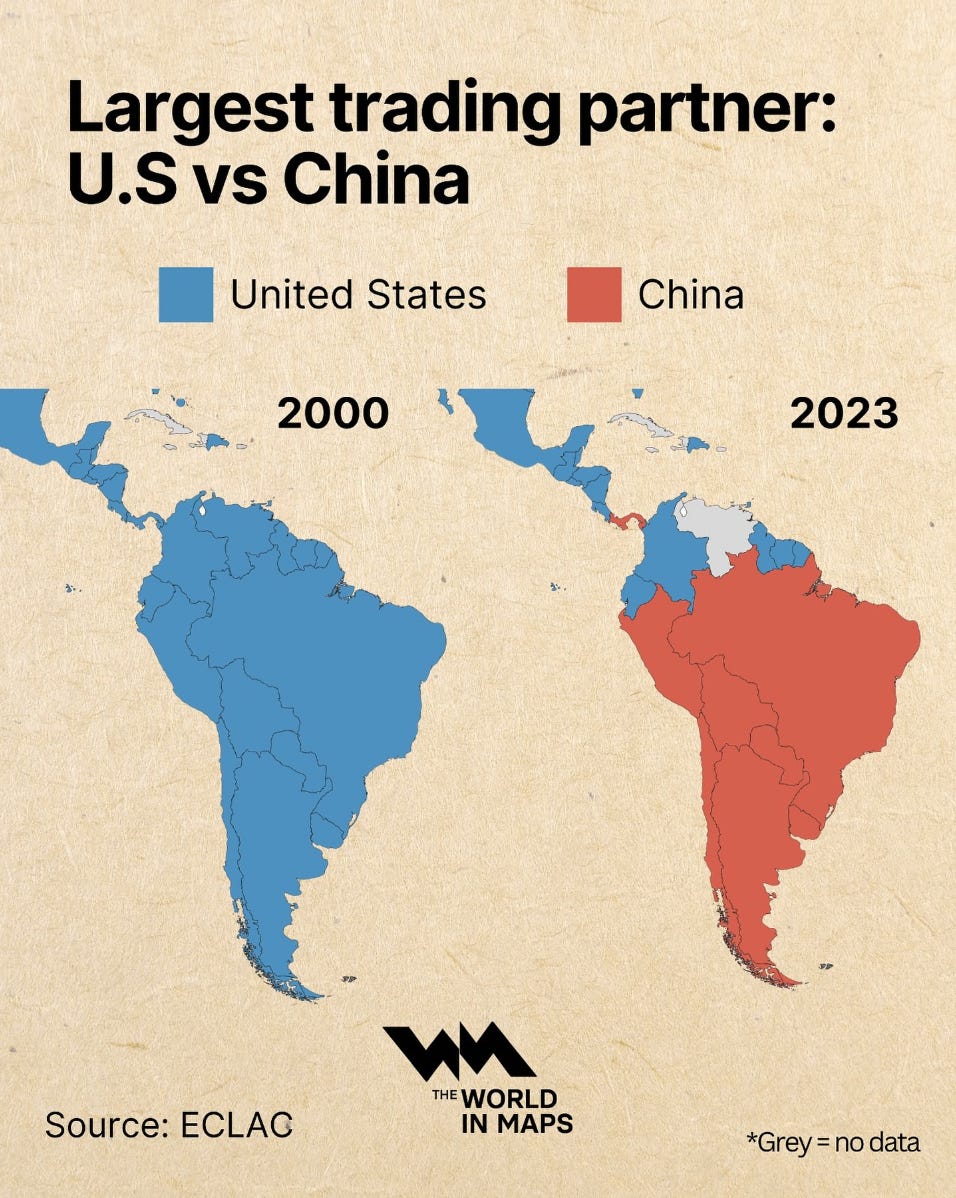

China embedded itself economically, becoming the largest trading partner for several Latin American economies, including Brazil. It financed ports, railways, power generation, and telecom networks. It became central to commodity flows that anchor fiscal and political stability.

These relationships are structural. They do not unwind quickly. This is the reality the U.S. is now re-entering.

A Modern Corollary: Economics over occupation

What we are witnessing today is not a return to 20th-century occupation, but a modernised Monroe Doctrine, enforced through economics, supply chains, and strategic alignment.

This shift was already visible in the 2025 U.S. National Security Strategy, which elevated the Western Hemisphere as a core security interest. Migration, supply chains, foreign influence, and economic resilience were fused into a single framework.

This week’s events in Venezuela make that posture unmistakable.

The message is clear. The hemisphere is no longer neutral ground, and that strategic assets, infrastructure, and political outcomes close to home matter again.

The Political complexity is real

For governments across Latin America, this moment is not abstract.

The reassertion of U.S. power, especially when it involves force, reopens historical memory. Central America, in particular, remembers what it meant when hemispheric stability was enforced rather than negotiated. Those memories shape domestic politics, constrain leaders’ room to manoeuvre, and complicate alignment.

At the same time, the economic reality has changed. China is no longer a peripheral partner; it is embedded in trade flows, infrastructure, and fiscal stability across much of the region. Disentangling from that relationship is neither realistic nor desirable in the near term.

This leaves governments walking a narrow path: maintaining strategic autonomy, preserving economic optionality, and avoiding the perception of subordination to either power.

That balance will not be easy. It will differ by country. And it will produce moments of friction; diplomatically, politically, and economically.

This is the context in which investors should read this weeks events: not as a reset, but as a re-weighting of constraints.

Why this is likely a net positive for Latin America economically

What is changing is not Latin America’s alignment, but its strategic relevance.

The United States is no longer treating the region as a background condition. It is re-integrating the hemisphere into its security, supply-chain, and economic planning; unevenly, selectively, and sometimes forcefully.

That does not eliminate China’s role. Nor does it guarantee stability or growth. But it does alter the incentive structure around capital, infrastructure, and integration with North American systems.

What does not change is that business integration follows a different logic than geopolitics.

Companies respond to: access to capital, regulatory clarity, supply-chain reliability, market proximity, standards and enforceability

To the extent U.S. re-engagement increases predictability along those dimensions, even imperfectly, it reshapes the operating environment for cross-border business.

For many sectors and countries, this could be beneficial. Let’s see what the rest of 2026 holds.

Until next time!

Archie, Victor and Bernardo

If you are interested in learning more about what we are building at Nascent, we would love to connect!

Archie@nascent.vc

Linkedin